Fluctuation-dissipation theorem

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem (FDT) is a powerful tool in statistical physics for predicting the behavior of non-equilibrium thermodynamical systems. These systems involve the irreversible dissipation of energy into heat from their reversible thermal fluctuations at thermodynamic equilibrium. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem applies both to classical and quantum mechanical systems.

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem relies on the assumption that the response of a system in thermodynamic equilibrium to a small applied force is the same as its response to a spontaneous fluctuation. Therefore, the theorem connects the linear response relaxation of a system from a prepared non-equilibrium state to its statistical fluctuation properties in equilibrium.[1] Often the linear response takes the form of one or more exponential decays.

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem was originally formulated by Harry Nyquist in 1928,[2] and later proven by Herbert Callen and Theodore A. Welton in 1951.[3]

Contents |

General applicability

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem is a general result of statistical thermodynamics that quantifies the relation between the fluctuations in a system at thermal equilibrium and the response of the system to applied perturbations.

The model thus allows, for example, the use of molecular models to predict material properties in the context of linear response theory. The theorem assumes that applied perturbations, e.g., mechanical forces or electric fields, are weak enough that rates of relaxation remain unchanged.

Brownian motion

For example, Albert Einstein noted in his 1905 paper on Brownian motion that the same random forces that cause the erratic motion of a particle in Brownian motion would also cause drag if the particle were pulled through the fluid. In other words, the fluctuation of the particle at rest has the same origin as the dissipative frictional force one must do work against, if one tries to perturb the system in a particular direction.

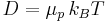

From this observation Einstein was able to use statistical mechanics to derive a previously unexpected connection, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation:

linking D, the diffusion constant, and μ, the mobility of the particles. (μ is the ratio of the particle's terminal drift velocity to an applied force, μ = vd / F). kB ≈ 1.38065 × 10−23 m2 kg s−2 K−1 is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

Thermal noise in a resistor

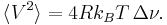

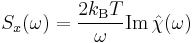

In 1928, John B. Johnson discovered and Harry Nyquist explained Johnson–Nyquist noise. With no applied current, the mean-square voltage depends on the resistance R,  , and the bandwidth

, and the bandwidth  over which the voltage is measured:

over which the voltage is measured:

General formulation

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem can be formulated in many ways; one particularly useful form is the following:

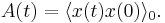

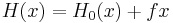

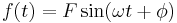

Let  be an observable of a dynamical system with Hamiltonian

be an observable of a dynamical system with Hamiltonian  subject to thermal fluctuations. The observable

subject to thermal fluctuations. The observable  will fluctuate around its mean value

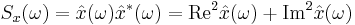

will fluctuate around its mean value  with fluctuations characterized by a power spectrum

with fluctuations characterized by a power spectrum  . Suppose that we can switch on a scalar field

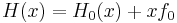

. Suppose that we can switch on a scalar field  which alters the Hamiltonian to

which alters the Hamiltonian to  . The response of the observable

. The response of the observable  to a time-dependent field

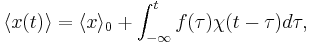

to a time-dependent field  is characterized to first order by the susceptibility or linear response function

is characterized to first order by the susceptibility or linear response function  of the system

of the system

where the perturbation is adiabatically switched on at  .

.

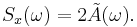

Now the fluctuation-dissipation theorem relates the power spectrum of  to the imaginary part of the Fourier transform

to the imaginary part of the Fourier transform  of the susceptibility

of the susceptibility  ,

,

.

.

The left-hand side describes fluctuations in  , the right-hand side is closely related to the energy dissipated by the system when pumped by an oscillatory field

, the right-hand side is closely related to the energy dissipated by the system when pumped by an oscillatory field  .

.

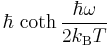

This is the classical form of the theorem; quantum fluctuations are taken into account by replacing  with

with  (whose limit for

(whose limit for  is

is  ). A proof can be found by means of the LSZ reduction, an identity from quantum field theory.

). A proof can be found by means of the LSZ reduction, an identity from quantum field theory.

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem can be generalized in a straight-forward way to the case of space-dependent fields, to the case of several variables or to a quantum-mechanics setting.

Derivation

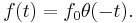

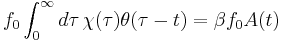

We derive the fluctuation-dissipation theorem in the form given above, using the same notation. Consider the following test case: The field f has been on for infinite time and is switched off at t=0

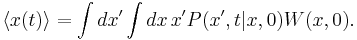

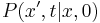

We can express the expectation value of x by the probability distribution W(x,0) and the transition probability

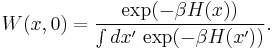

The probability distribution function W(x,0) is an equilibrium distribution and hence given by the Boltzmann distribution for the Hamiltonian

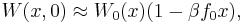

For a weak field  , we can expand the right-hand side

, we can expand the right-hand side

here  is the equilibrium distribution in the absence of a field. Plugging this approximation in the formula for

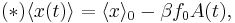

is the equilibrium distribution in the absence of a field. Plugging this approximation in the formula for  yields

yields

where A(t) is the auto-correlation function of x in the absence of a field.

Note that in the absence of a field the system is invariant under time-shifts. We can rewrite  using the susceptibility of the system and hence find with the above equation (*)

using the susceptibility of the system and hence find with the above equation (*)

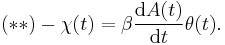

Consequently,

For stationary processes, the Wiener-Khinchin theorem states that the power spectrum equals twice the Fourier transform of the auto-correlation function

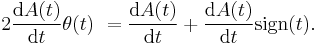

The last step is to Fourier transform equation (**) and to take the imaginary part. For this it is useful to recall that the Fourier transform of a real symmetric function is real, while the Fourier transform of a real antisymmetric function is purely imaginary. We can split  into a symmetric and an anti-symmetric part

into a symmetric and an anti-symmetric part

Now the fluctuation-dissipation theorem follows.

Violations in glassy systems

While the fluctuation-dissipation theorem provides a general relation between the response of equilibrium systems to small external perturbations and their spontaneous fluctuations, no general relation is known for systems out of equilibrium. Glassy systems at low temperatures, as well as real glasses, are characterized by slow approaches to equilibrium states. Thus these systems require large time-scales to be studied while they remain in disequilibrium.

In the mid 1990s, in the study of non-equilibrium dynamics of spin glass models, a generalization of the fluctuation-dissipation theorem was discovered that holds for asymptotic non-stationary states, where the temperature appearing in the equilibrium relation is substituted by an effective temperature with a non-trivial dependence on the time scales. This relation is proposed to hold in glassy systems beyond the models for which it was initially found.

See also

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamics

- Green-Kubo relations

- Onsager reciprocal relations

- Equipartition theorem

- Boltzmann factor

- Dissipative system

Notes

- ^ David Chandler (1987). Introduction to Modern Statistical Mechanics. Oxford University Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0195042771.

- ^ Nyquist H (1928). "Thermal Agitation of Electric Charge in Conductors". Physical Review 32: 110–113. Bibcode 1928PhRv...32..110N. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.32.110.

- ^ H.B. Callen, T.A. Welton (1951). "Irreversibility and Generalized Noise". Physical Review 83: 34–40. Bibcode 1951PhRv...83...34C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.83.34.

References

- H. B. Callen, T. A. Welton (1951). "Physical Review". Physical Review 83: 34. Bibcode 1951PhRv...83...34C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.83.34.

- L. D. Landau, E. M. Lifshitz. Physique Statistique. Cours de physique théorique. 5. Mir.

- Umberto Marini Bettolo Marconi; Andrea Puglisi; Lamberto Rondoni; Angelo Vulpiani (2008). "Fluctuation-Dissipation: Response Theory in Statistical Physics". Physics Reports 461 (4–6): 111–195. arXiv:0803.0719. Bibcode 2008PhR...461..111M. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2008.02.002.

Further reading

- Audio recording of a lecture by Prof. E. W. Carlson of Purdue University

- Kubo's famous text: Fluctuation-dissipation theorem

- Weber J (1956). "Fluctuation Dissipation Theorem". Physical Review 101 (6): 1620–1626. Bibcode 1956PhRv..101.1620W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.101.1620.

- Felderhof BU (1978). "On the derivation of the fluctuation-dissipation theorem". Journal of Mathematical Physics A 11 (5): 921–927. Bibcode 1978JPhA...11..921F. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/11/5/021.

- Chandler D (1987). Introduction to Modern Statistical Mechanics. Oxford University Press. pp. 231–265. ISBN 978-0195042771.

- Reichl LE (1980). A Modern Course in Statistical Physics. Austin TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 545–595. ISBN 0-292-75080-3.

- Plischke M, Bergersen B (1989). Equilibrium Statistical Physics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 251–296. ISBN 0-13-283276-3.

- Pathria RK (1972). Statistical Mechanics. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 443, 474–477. ISBN 0-08-018994-6.

- Huang K (1987). Statistical Mechanics. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 153, 394–396. ISBN 0-471-81518-7.

- Callen HB (1985). Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 307–325. ISBN 0-471-86256-8.